Supraventricular Arrhythmias

The commonest postoperative arrhythmia in Thoracic Surgery is fast atrial fibrillation, with atrial flutter a close second. Usually it is relatively harmless but if allowed to remain at a high rate for too long, can cause heart failure and death. It really worries the patient who “feels yuck”, breathless and frequently has chest tightness (and therefore thinks they are having a heart attack).

The definitive paper on this topic is:

-

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Practice Guideline on the Prophylaxis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation Associated With General Thoracic Surgery: Executive Summary. Hiran C et al. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:1144–52

Causes

We don’t know what causes postop atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. The commonest listed in textbooks are:

-

•Ischaemic heart disease - ironically in an audit of our own lung resections, the bad IHD patients who had maximal B Blockers, BP control etc, were the least likely to get postop AF

-

•Hypoxia - exacerbates myocardial ischaemia

-

•Pericardial irritation - particularly in intrapericardiac pneumonectomy

-

•Mediastinal shift - especially in pneumonectomy where there is up to 50% incidence

-

•Bronchodilators - Salbutamol usually causes sinus tachycardia not AF. Be slow to attribute the tachycardiac to bronchodilators till other diagnoses have been excluded. Other bronchodilators such as Atrovent and Pulmicort are less arrhythmogenic.

-

•Pain - will cause sinus tachycardia but will also increase sympathetic output and myocardial irritability.

-

•Hypokalaemia - a common cause due to prescription of fluids without adequate K+ replacement, but also due to administration of diuretics without K+ supplementation. For membrane stabilisation the K+ should be higher than the normal range. The lower limit of normal for potassium on the Thoracic Unit is 4.5.

-

•Hypomagnesaemia - Magnesium is also important for membrane stabilisation. Though the lower limit of normal is 0.75 mmol/l, one should remember that at 0.75, statistically 95% of the population has a higher Mg level than your patient. If anyone should be in the TOP 5% it is the post-thoracotomy patient.

Other credible causes, probably of more relevance in lung and oesophageal surgery are:

-

•Injury to the vagal nerves: full dissection of the hilum involves dividing most of the vagal fibres to the heart. similarly, oesophagectomy (>50% develop AF, independently of mediastinitis) involves a complete vagotomy. The vagi have a negative chronotopic effect on the heart. Injury to the vagi would be expected to reduce such an effect and increase tachyarrhythmias.

-

•Irritation of arrhythmogenic foci in the pulmonary veins - the proximal pulmonary veins are involved in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. This is born out by the success of the Cox Maze procedures used to ablate these foci. It should come as no surprise that an operation that involves dissection and division of the pulmonary veins has such an incidence of tachy-arrhythmias.

These effects are known to last approximately 6-8 weeks following Thoracic Surgery. Interestingly this is the period of hypersensitivity reported by cardiac surgeons performing pulmonary vein ablation for paroxysmal AF.

However none of these individually explains why a patient with a chest drain for pneumothorax, or who has a small peripheral wedge resection gets AF. So in most patients it is multifactorial.

Prevention

-

•Do not stop B Blocker peri-operatively. Some may need IV maintenance.

-

•Maintain oxygenation - Thoracic patients benefit from supplemental oxygen for 3-5 days postop regardless of SaO2

-

•Maintain adequate K+. The lower limit of normal for potassium on the Thoracic Unit is 4.5 (not 3.5 as used for normal community)

-

•Maintain adequate Mg++

Anticipating

The patient will frequently have runs of atrial ectopics in the evening before going into AF in the middle of the night. If you see that, correct electrolytes and oxygenation and consider starting anti-arrhythmics e.g. digitalisation. You may prevent a call in the middle of the night. What is good for you is good for your patient!

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO:

-

1.Re-assure the patient you will be able to help

-

2.Administer oxygen by face mask

-

3.Ensure a working IV line and administer bolus of fluid (250cc)

-

4.Take blood for K+ and correct any deficiency less than 4.5 mmol/L. (correction should be over 1-2 hours and not as a 24 hour infusion)

-

5.Take blood for Mg++ and correct any deficiency less than 1.0 mmol/L. (correction should be over 1-2 hours and not as a 24 hour infusion)

-

6.Take blood for drug levels (e.g. Digoxin levels if on Digoxin)

-

7.Take blood for cardiac enzymes

-

8.Take 12 lead ECG with a rhythm strip adequate to tell the true rhythm

-

9.Administer drugs to reduce the heart rate to <110/min (all intravenous anti-arrhythmic drugs should be given with constant cardiac monitoring)

-

10.Start a regime to maintain the heart rate between 80 and 110/min

-

11.Look for other causes of tachycardia - sepsis, anastomotic leak from oesophagus, pneumothorax, hypotension, bleeding etc.

-

12.Contact the Thoracic Registrar on call, NOT cardiology

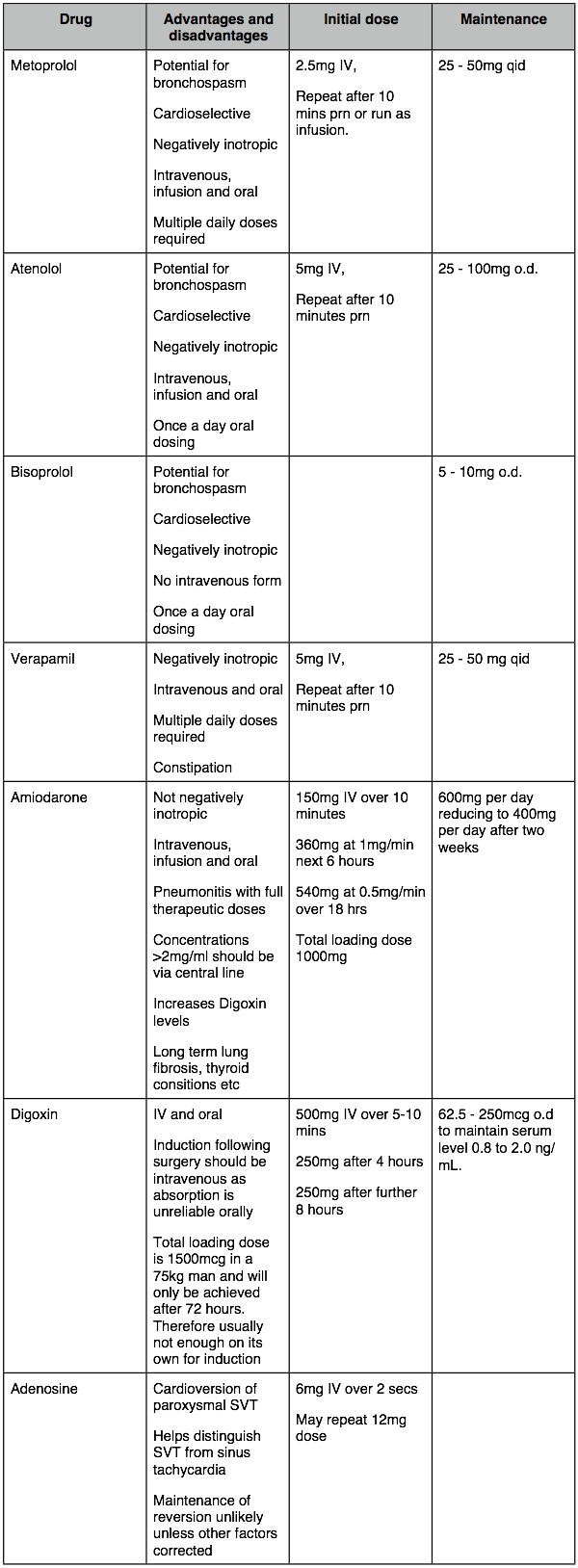

Which drugs?

-

‣B Blockers: - B Blockers are excellent for rate control. There has been some reluctance using them in patients with respiratory disease (i.e. most Thoracic patients). While due caution should be paid to respiratory disease, most of our patients do not suffer from reversible bronchospastic disease (asthma). Rather, they have relatively irreversible chronic bronchitic and emphysematous changes, have maximal bronchodilator therapy and generally are not sensitive to B blockers. However, it is wise to restrict usage to cardioselective B blockers like metoprolol (IV and oral), atenolol (IV and oral), bisoprolol (oral) and esmolol (IV short acting). These have been shown to be generally safe in clinical usage. Generally do not revert to sinus but control rate. Can be continued orally for maintenance.

-

‣Verapamil: - was the standard agent for reducing rate prior to the use of amiodarone and cardio-selective B blockers. Verapamil is not favoured by cardiac surgeons because of the potential for a negative inotropic effect. It is effective but requires repeat IV boluses.

-

‣Digoxin: - has virtually no effect on rate till serum levels start to stabilised after 6 -8 hours. Full digitalisation is not achieved till 72 hours. It is therefore more useful for maintenance than acute treatment of arrhythmia.

-

‣Amiodarone: - favoured by cardiologists and cardiac surgeons who prescribe it automatically when SVT occurs. It does not have the negatively inotropic effect of verapamil nor the respiratory side effects of B blockers and the rate of the infusion can be changed over the phone!. It does, however, have potentially serious pulmonary complications following lung resection - DO NOT USE AMIODARONE AS FIRST LINE THERAPY IN LUNG RESECTION PATIENTS. (see below)

Anticoagulation

The question of anticoagulation arises in all patients with AF. The usual warfarinisation that is recommended in new diagnosis of AF has to be balance with the risks of peri-operative bleeding, especially on removal of drains and epidural cannulae. Most of our surgical patients are on significant heparinoid anticoagulation over this period. Most are only n AF for a few days and revert prior to discharge. Our current approach, without the proof of an evidence base, is that on balance they do not need any anticoagulation over and above normal perioperative Clexane.

Standard cardiology measures:

These work if the underlying causes have been resolved which is the situation in the elective cardiology patient. However, that is rarely the case in Thoracic Surgery.

Most of these measures will have no persistent effect as the underlying causes - hypoxia, vagal ablation, pulmonary vein irritation will not be reversed.

-

•Carotid massage - may be attempted but will only be a short-term measure,

-

•Adenosine is used to differentiate a sinus tachycardia from SVT - it is an interesting curiosity but of little more in Thoracic Surgery.

-

•DC conversion - unlikely to maintain SR. Patient usually reverts to AF. Frequently delays other more appropriate treatments. (For those who are interested in anecdote, I have not had any patient successfully DC converted acutely following thoracotomy.)

-

•Amiodarone is a great anti arrhythmic. It works. If it is not working you can ask the nurse to increase the rate of infusion over the phone while you stay in bed. It also rots lungs! Long term it has a wide range of effects from thyroiditis to pneumonitis which can be worse than the disease. It is best avoided in lung resections except as a second line drug and should be cleared with a consultant before use. A full therapeutic dose of amiodarone in a pneumonectomy patient with pre-existing interstitial lung disease may be enough to tip them over into ARDS from which they do not survive (Van Meighem 1994, Greenspon 1991, Kay 1988, Olshansky 2005). BE CAUTIOUS ABOUT USING AMIODARONE AS FIRST LINE THERAPY IN LUNG RESECTION PATIENTS.

Prophylaxis

Attempts using Digoxin to prevent postop AF in lung and oesophageal surgery have not been successful (see references below from this unit). One paper from Memorial Sloan Kettering suggests that full loading with Diltiazem can reduce the incidence in high risk patients:

References:

1.Ritchie AJ, Tolan M, Whiteside M, McGuigan JA, Gibbons JR. Prophylactic digitalization fails to control dysrhythmia in thoracic esophageal operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993 Jan;55(1):86-8.

2.Ritchie AJ, Whiteside M, Tolan M, McGuigan JA. Cardiac dysrhythmia in total thoracic oesophagectomy. A prospective study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1993;7(8):420-2.

3.Ritchie AJ, Danton M, Gibbons JR. Prophylactic digitalisation in pulmonary surgery. Thorax. 1992 Jan;47(1):41-3.

4.Ritchie AJ, Bowe P, Gibbons JR. Prophylactic digitalization for thoracotomy: a reassessment. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990 Jul;50(1):86-8.

5.Amar D, Roistacher N, Rusch VW, Leung DH, Ginsburg I, Zhang H, Bains MS, Downey RJ, Korst RJ, Ginsberg RJ. Effects of diltiazem prophylaxis on the incidence and clinical outcome of atrial arrhythmias after thoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000 Oct;120(4):790-8.

6.Van Mieghem W, Coolen L, Malysse I, Lacquet LM, Deneffe GJ, Demedts MG. Amiodarone and the development of ARDS after lung surgery. Chest 1994;105:1642–5.

7.Greenspon AJ, Kidwell GA, Hurley W, Mannion J. Amiod- arone-related postoperative adult respiratory distress syn- drome. Circulation 1991;84(Suppl 3):407–15.

8.Kay GN, Epstein AE, Kirklin JK, Diethelm AG, Graybar G, Plumb VJ. Fatal postoperative amiodarone pulmonary tox- icity. Am J Cardiol 1988;62:490–2.

9.Olshansky B, Sami M, Rubin A, et al. Use of amiodarone for atrial fibrillation in patients with preexisting pulmonary disease in the AFFIRM study. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:404–5.

10.Hiran C. Fernando, MD, Michael T. Jaklitsch, MD, Garrett L. Walsh, MD, James E. Tisdale, PhD, Charles D. Bridges, MD, ScD, John D. Mitchell, MD, and Joseph B. Shrager, MD. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Practice Guideline on the Prophylaxis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation Associated With General Thoracic Surgery: Executive Summary. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:1144–52